In the last post I wrote about the family background of my 4 x great grandfather James Blanch, father of John Blanch who married Keziah Holdsworth. James was born in Tewkesbury in 1755, the eldest of the three sons of Thomas and Mary Blanch, a Quaker couple who spent most of their married life in Bristol. Thomas Blanch was a patten maker, like his father before him, and all three of his sons took up the same occupation. As I noted at the end of the last post, those three sons – James, Thomas and William – also moved from Bristol to London, though William appears to have returned to his home city at some point.

James Blanch in Soho and Ealing

James, being the eldest of the three, was the first to arrive in London. I’m fairly certain that he was apprenticed to the man whose daughter he would eventually marry. William Barlow was a patten maker in Compton Street, Soho (where, coincidentally, my paternal great grandfather Charles Edward Robb would be born in 1851). He and his wife Elizabeth had a son, William, and five daughters who survived to adulthood: Mary, Jane, Hannah, Anne and Margaret.

William Barlow the younger, a patten maker like his father, married Sarah Egginton. Hannah married Henry Davis, a coach maker from Little Tottenham Street, off Tottenham Court Road, while her sister Mary married Thomas Gatton, a cheesemaker in Wardour Street. Ann Barlow married Simon Sharpe, originally from Witney, Oxfordshire, and her sister Margaret married Charles Lees and lived in Edgeware.

That leaves Jane, who had been born on 23rd January 1752 and christened in the parish church of St Anne, Soho on 9th February that year. She would marry James Blanch, but not until after her father William’s death. Curiously, William Barlow’s will makes no reference to James, despite the fact that the will was made in November 1778, that he would die in August 1779, and that James and Jane would marry just a few weeks later, on 5th September. Instead, Barlow’s will contains a number of references to another James – a certain ‘James Frith the Younger of Sheppards Market in the parish of St George Hanover Square in the … County of Middlesex Grocer’ – usually alongside references to his daughter Jane. For example, Barlow makes Jane and James Frith co-executors of the will, and decrees that together they are to inherit his property in Ealing, as well as a number of other properties in London. We learn from the will that while William Barlow’s main address was in Compton Street, Soho, he also owned other properties in Westminster – in Wardour Street, Poulteney Street and in Cross Lane, off Long Acre – as well as ‘my Freehold Lands Messuages Tenements and Hereditaments situate and being at Castle Bear in the parish of Ealing’.

James Frith seems to have been the son of the man Barlow refers to in the will as ‘my friend Mr James Frith the Elder’. The most likely explanation is that Jane Barlow and James Frith the younger were engaged to be married at the time William Barlow made his will, making it legitimate for him to treat them as a single (and the principal) beneficiary of the will. If this is so, we will probably never know why, following her father’s death, Jane decided to marry a different James –my ancestor James Blanch – instead. Perhaps the marriage to Frith had been Jane’s father’s idea rather than her own – an arrangement between William and his good friend James Frith the elder, perhaps – and her preference had been for James Blanch all along. In the event, James Frith married a different Jane – Jane Atkinson – in December 1779; he would die in 1794.

Marriage allegation and bond for James Blanch and Jane Barlow, September 1779 (via ancestry.co.uk)

On 3rd September 1779 James Blanch, a heel maker and bachelor of the parish of St Anne, Westminster applied for a licence to marry Jane Barlow, a spinster of the same parish. The wedding took place two days later at St Anne’s church. The witnesses were William Dorrell and John Elcock, both of whom lived, like the Barlows, in Compton Street. John Elcock was a carver and also a parish official (he was an overseer of the poor) whose name appears on other marriage records in the St Anne’s register. He may well have been a neighbour and family friend, but equally he may simply have signed the register in an official capacity.

William Dorrell, on the other hand, had no official connection with the church: in fact, he was a Quaker, and his presence at the wedding suggests that James maintained his Quaker connections after coming to London. Dorrell was a watch and clock-maker, from a long line of men following this highly-skilled trade. The record for the birth of one of his children shows that he and his wife Eleanor belonged to the (Quaker) Quarterly Meeting of London and Middlesex.

According to one source, ‘William undertook several jobs of work for Thwaites of London’ and ‘in 1797, restored Cripplegate church clock and made it strike the hours on the tenor bell’. The same source informs us that Dorrell ‘was declared bankrupt in 1798, but obviously got his business back together, because, as a result of an advert in a London paper, he won a contract in 1805 to repair the clock and chimes in Tewkesbury Abbey, Gloucester. To repair the clock and chimes and replace 2 dials he charged £207 8s 0d. The chime barrel was made to play 3 tunes.’ The fact that William Dorrell’s neighbour, my ancestor James Blanch, was born in Tewkesbury and that members of his family had close connections with the abbey cannot be coincidental.

Clock made by William Dorrell, restored by Mike Newcombe (via http://www.mikenewcombe.co.uk)

The next record that we have for James Blanch after his marriage to James Barlow is the poll book for the Westminster election of the following year, 1780, when the couple were living in Compton Street, almost certainly in the house formerly owned by Jane’s father William. The property is given a rack rent value of £26. James is described in the poll book as a patten maker and we learn that he voted for the radical Whig politician Charles James Fox, who was returned for the prestigious Westminster constituency with a large majority.

On 26th Mary 1780, James and Jane Blanch’s first child, also named James, was christened at St Anne’s church, Soho. In the following year, James was selected to serve as a member of a coroner’s jury in the parish. In the same year, James Blanch junior died – he was not quite a year old – and was buried at St Anne’s on 3rd April 1781. In the summer of that year, Jane gave birth to a daughter, Maria, who was christened on 17th July.

Two years later, in 1783, James was again a member of a coroner’s jury in the parish of St Anne’s, and on 2nd April that year, he and Jane had a second daughter, Elizabeth, christened at the parish church. When James voted in the Westminster election of 1784, he was still living in Compton Street and working as a patten maker. This time he hedged his bets and voted for both the Tory Samuel Hood and the Whig Sir Cecil Wray. On 17th November 1784 a second son with the name James was christened at St Anne’s.

James Blanch’s vote for Charles James Fox (‘F’) registered in the Westminster Poll Book of 1780 under Compton Street (via ancestry.co.uk)

In 1786, James Blanch was still living in Compton Street when he joined another coroner’s jury. However, by the time of the 1790 Westminster election, he had moved to Cross Lane, off Long Acre, in the neighbouring parish of St Martin-in-the-Fields, probably to the house in that street mentioned in the will of his late father-in-law. On this occasion he voted for the controversial John Horne Tooke, who was defeated and later tried for (and acquitted of) treason. James’ support for radical candidates is unsurprising, given his Quaker background. As I noted in the last post, Quakers were in the forefront of a number of campaigns for social and political reform in the eighteenth century. The naturalist Simeon Warner Millard, nephew of James’ stepmother Sarah Millard, got into trouble for publishing an address to the inhabitants of Tewkesbury, opposing the practice of illuminating for national victories in battle, while another nephew, Moses Goodere of Worcester, faced mob violence for supporting an act of parliament that aimed to improve the conditions of the poor.

As well as occupying houses in Westminster, James and Jane Blanch also seems to have inherited William Barlow’s property at Castle Bar or Bear, Ealing. James was certainly paying land tax on a house there in 1787. He is named as the occupier of the property, paying £1 in tax, though curiously the proprietor is said to be ‘Mr Barlow or Blanch’. This confusion may simply be due to the fact that the property formerly belonged to his late father-in-law, or it might have been registered originally in Jane Barlow’s maiden name. There are also records for the same property for 1788, when the proprietor is clearly James himself and the tax is still £1, and for 1789 when the figure is 17s 6d.

Land tax records for ‘Castle Bear’, Ealing, in 1787 (via ancestry.co.uk)

The tax records show that James Blanch’s house was one of only nine in the village of Castle Bar. Three of the proprietors, including James, were plain ‘Mr’, while the others were ‘Esquire’, i.e. fully fledged ‘gentlemen’. I wonder if one of them, Francis Burdett Esquire, was the reformist politician of that name (who, interestingly, was the mentor of John Horne Tooke, for whom James Blanch voted in 1790)? Another neighbour was Mr Thomas Scotland: there was an attorney with that name active in London at this time. In other words, this was a prestigious address, which makes James Blanch’s later move to the decidedly less salubrious district of Saffron Hill in Holborn difficult to understand (see the next post).

William Blanch in London, Bristol and Bath

In 1789 James Blanch and his younger brothers Thomas and William were all made Freemen of the City of Gloucester. Apparently, one could become a freeman in one of four ways: by apprenticeship, by patrimony, by purchase or by gift of the city corporation. In the case of the Blanch brothers, it would appear that they became freemen by patrimony: in other words, they inherited the status from their father Thomas, a patten maker in Bristol. Moreover, although Gloucester is specified, it is clear that the title was given to men from elsewhere in the county, including Bristol.

(image via amazon.co.uk)

Interestingly, the entry for James Blanch in the Register of the Freemen of the City of Gloucester describes him as ‘Jas. Blanch, patten-maker, of Castlebar, Ealing, Mdx., son of Thos., patten-maker, of Bristol’. In other words, for this purpose at least, James was using the property in Castle Bar that he and Jane had inherited from her father William as his main address.

Even more interestingly, James’ younger brother William, another patten-maker, is also described in the register as being of ‘Castlebar, Ealing, Mdx.’. So William must also have moved to London and at this time was living, and perhaps working, with his older brother James. However, by 1795 William would be listed in a Bristol trade directory, describing him as a patten maker in New Street. In fact, all the later records we have for William place him either in Bristol or in Bath, so he must have left London and moved back to the West Country at some point. William Blanch was married two, or possibly three times. With his first wife Margaret he had three children, all born in Bristol: James in 1796; Margaret, 1797; and William, 1800. The marriages in Bristol between William Blanch and Rachel Bryan in 1803, and between William Blanch and Mary Allen in 1806 may relate to him.

I don’t know what became of William Blanch junior, but his sister Margaret married Daniel Smith in Bristol in 1815. As for William Blanch’s son James, he married Elizabeth Redwood in the same year, and they would have at least eight children together. James was an ironmonger, firstly in Bristol and later in Bath. In 1816, James Blanch, ironmonger, son of William, patten-maker of Bristol, formerly of Castle Bar, Ealing, Middlesex, was made a freeman of the City of Gloucester. The 1818 electoral register for Somerset includes the name of James Blanch, an ironmonger of Bath, followed by that of William Blanch, a patten maker, also of Bath, suggesting that William may have gone to live with his son in his later years.

Thomas Blanch in Holborn

The Register of the Freemen of the City of Gloucester notes that ‘Thos. Blanch, heelmaker, son of Thos., heelmaker, of Bristol’ was also made free in 1789. This was Thomas, the other brother of my ancestor James. He also moved to London as a young man, but doesn’t seem to have lived with James and William at Castle Bar. Before coming to the city, Thomas married Sarah Clark in Bristol: the marriage took place on 17th October 1785, when Thomas would have been nineteen years old.

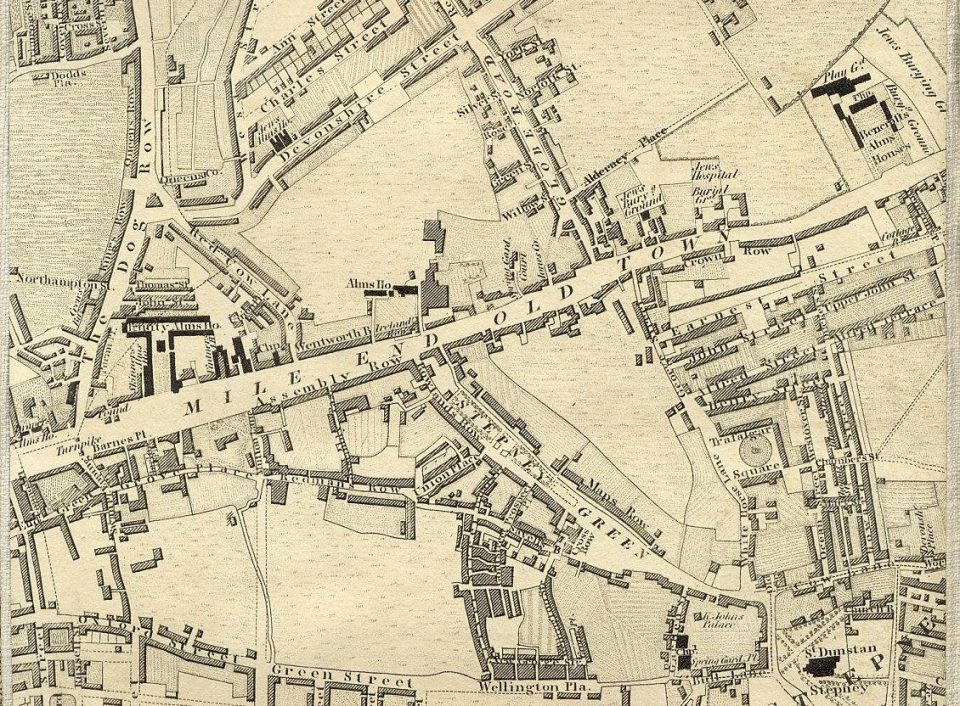

Part of Richard Horwood’s 1792 map of London, showing the area around Saffron Hill, Holborn (via http://www.motco.com/map/81005/)

It’s unclear when Thomas and Sarah Blanch moved from Bristol to London, but they were certainly there by November 1791, when their daughter Louisa was born. She was christened at the church of St Giles, Cripplegate, but by the time the couple’s next child, Harriet Matilda, was born, in October 1795, they had moved to Fetter Lane in Holborn. They were living in the same area, but now in Saffron Hill, when their son Thomas was born in May 1807, and their daughter Sarah Ann Catherine was christened in 1812 (though she had been born in 1803). Harriet, Thomas and Sarah were all baptised at the parish church of St Andrew, Holborn. Thomas and Sarah Blanch also had a son named Alfred, a patten maker like his father, who was made a freeman in 1816, so may have been born before the family left Bristol.

The death of Jane Blanch

My 4 x great grandfather James Blanch would follow his brother Thomas to Holborn, following the death of his first wife Jane and his second marriage to Sophia Atkins. We don’t know exactly how or when Jane died, but it must have been some time between the birth of her son James Blanch junior in 1784, and James senior’s marriage to Sophia in 1792. I’ll discuss that marriage and the family’s move from Soho to Holborn in the next post.