My 4 x great grandfather, Tewkesbury-born patten maker James Blanch, married his second wife, my 4 x great grandmother Sophia Atkins, at the parish church of St Anne, Soho, on 21st March 1792. James signed his name but Sophia was only able to make a mark in lieu of a signature. Bride and groom were both said to be ‘of this parish’. Sophia’s origins are obscure, but since she was forty-four years old when she died in 1821, it’s possible that she was the daughter of Thomas and Hannah Atkins who was born in the parish of St Mary’s, Bromley St Leonard, to the east of London, in 1778. However, that would mean that Sophia was only fourteen when she married James Blanch, a widower of thirty-six with three young children – Maria, eleven; Elizabeth Ann, nine; and James, eight. It prompts the question as to how James and Sophia met: was she perhaps a servant in the Blanch household, or the daughter of a business associate?

In the last post I noted that James and his first wife Jane seem to have inherited a number of properties in Westminster from Jane’s father William Barlow, as well as a fairly prestigious suburban address in the village of Castle Bar, Ealing. However, James’ fortunes appear to have changed following Jane’s death, and soon after his marriage to Sophia the family moved away from Soho, first to Southwark and then to Holborn, where James’ younger brother and his family were already living.

Church of St George the Martyr, Southwark

James and Sophia Blanch’s first child, Mary Ann, was born two years after their marriage, on 6th May 1794, at St George’s Fields, Southwark, and christened at the parish church of St George the Martyr on 1st August. By the time their next child, a son named Thomas, was christened, at St Andrew’s church, Holborn, on Boxing Day, 1797, James and Sophia had moved again, to Saffron Hill, where James’ brother, also named Thomas, and his family were probably already living (they were in nearby Fetter Lane in 1795 and would definitely be at Saffron Hill by 1807 at the latest).

Contemporary descriptions of Saffron Hill only deepen the mystery of how a once-prosperous tradesman like James Blanch came to be living there. A guide to London published in 1878 described the area in these terms:

Northward from Field Lane ran Saffron Hill, which once formed a part of the pleasant gardens of Ely Place, and derived its name from the crops of saffron which it bore. But the saffron disappeared, and in time there grew up a squalid neighbourhood, swarming with poor people and thieves. Strype, in 1720, describes the locality as ‘of small account both as to buildings and inhabitants, and pestered with small and ordinary alleys and courts taken up by the meaner sort of people; others are,’ he says, ‘nasty and inconsiderable.’

In 1838 Charles Dickens would write this in Oliver Twist:

Near to the spot on which Snow Hill and Holborn Hill meet, there opens, upon the right hand as you come out of the City, a narrow and dismal alley leading to Saffron Hill. In its filthy shops are exposed for sale huge bunches of second-hand silk handkerchiefs, of all sizes and patterns; for here reside the traders who purchase them from pickpockets.

And in 1850, Peter Cunningham wrote about Saffron Hill in his Hand-Book of London:

A squalid neighbourhood between HOLBORN and CLERKENWELL, densely inhabited by poor people and thieves. It was formerly a part of Ely-gardens, and derives its name from the crops of saffron which it bore. It runs from Field-lane into Vine-street, so called from the Vineyard attached to old Ely House. The clergymen of St. Andrew’s, Holborn, (the parish in which the purlieu lies), have been obliged, when visiting it, to be accompanied by policemen in plain clothes.

Curiously, James and Sophia Blanch were back in Soho for the christening of their daughter Sophia Sarah at St Anne’s church on 2nd September 1799. The child would live for less than a year, being buried on 21st August 1800. The place of burial – the Countess of Huntingdon’s Chapel at Spa Fields, Clerkenwell – confirms that James Blanch retained his Nonconformist connections, even if he was no longer an active Quaker.

Saffron Hill in the nineteenth century (date of photograph unknown)

James and Sophia Blanch were at Saffron Hill once again in August 1802, when their son John, my 3 x great grandfather, was christened at St Andrew’s church. They were said to be living in nearby York Street when another son, William Henry, was born in 1804, and they were still there when their youngest sons Joseph and David were born in 1807 and 1810 respectively.

In the last post I noted that James Blanch and his brothers Thomas and William had been made freemen of the City of Gloucester in 1789. In 1816 it was the turn of the next generation, with one son of each of these three men receiving their freedom from the same source. These were William’s son James, an ironmonger in Bristol and then Bath; Thomas’ son Alfred, a patten-maker in London; and James’ son Thomas, also a patten maker.

The poll book for the Gloucester city election of 1818 lists all those entitled to vote, including those who were resident elsewhere in the country. According to British History Online:

The expense of contested elections was much increased by the cost of tracing and canvassing the large number of outvoters, Gloucester freemen living in other parts of the country: of the 1,579 freemen who voted in 1816, only 562 lived in the city.

The same website notes that it was only with the Reform Act of 1832 that ‘freemen living more than seven miles from the city’ were disenfranchised, and that from that time only freemen qualifying by birth or apprenticeship were qualified to vote. The entry for ‘London and vicinity’ includes five men with the surname Blanch:

(Via Ancestry.co.uk)

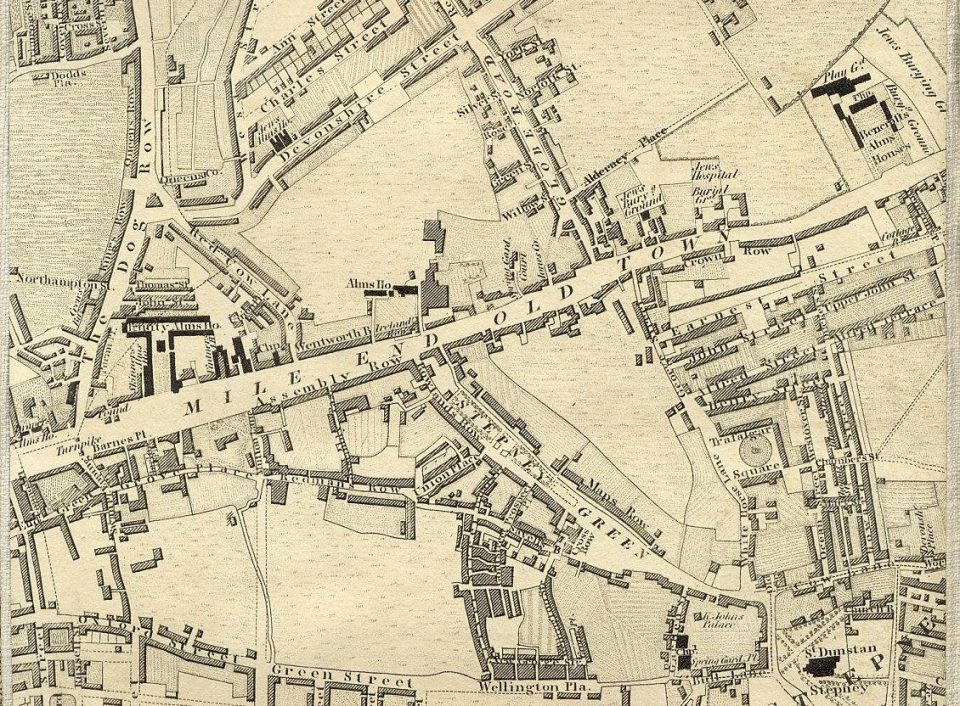

I assume that Alfred was the son of James’ brother Thomas; James was my ancestor, even though he is now said to be living at nearby Hatton Wall rather than York Street or Saffron Hill; John may have been James’ son, though he would only have been sixteen at the time; the two Thomases must be James’ brother and his son, though which of them was living at Hatton Wall and which in Stepney is unclear.

There were three candidates for the Gloucester constituency in the general election of 1818: Edward Webb and Maurice Frederick Berkeley, both Whigs, and Robert Bransby Cooper, a Tory. Cooper was elected with Webb, while Berkeley was unsuccessful. If I read the electoral register correctly, then all of my Blanch ancestors voted for Cooper, which is surprising, given James Blanch’s votes for Whigs and radicals in earlier elections. The fact that all of these men voted for the same candidate is perhaps further confirmation that they belonged to the same family, or it may be evidence of successful long-distance campaigning (or patronage?) by Cooper.

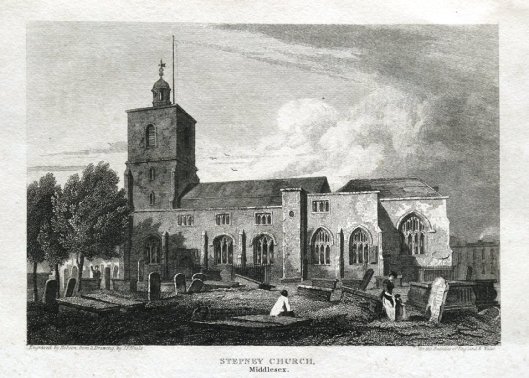

James’ wife Sophia Blanch née Atkins died in 1821 and was buried on 28th January at the parish church of St Dunstan and All Saints, Stepney. She was forty-four years old. The parish register gives the cause of her death as asthma. It also states that Sophia was living in Mile End Old Town at the time of her death. It’s unclear whether she and James had moved there from Holborn at some point, or whether Sophia was simply staying with relatives, perhaps one of her children, at the time of her death.

As for James Blanch, he lived for another nineteen years, dying on 18th December 1840 at the age of eighty-six years. He was buried alongside his wife Sophia at St Dunstan’s, Stepney, though he is said to have died at 21 King Street, Soho, the home of his son David. The cause of death is given in the parish register simply as ‘age’.

Interestingly, James’ death certificate suggests that, in the latter years of his life, he had left behind his work as a patten maker and found work as a Custom House officer, or as his probate certificate has it, an exciseman. As I mentioned in an earlier post (and will discuss in detail in a later one), this had also been the occupation of his son, James Blanch junior, until the latter’s conviction for theft and transportation to Australia in 1814.

For some reason, James Blanch senior’s will was not proved until July 1959, some nineteen years after his death. He left effects under £200 in value and the will was proved by the oath of Richard Ellis, a carpenter, and one of James’ executors. The connection between the Blanch and Ellis families was deep and longstanding, but also mysterious: I’ll attempt to throw light on it in the next few posts, in which I’ll explore the lives of the children of James Blanch.